Lying in his beds damping with folded sheets and towels, Babutty, the star of yesteryear among the artists of Circus of Thalassery, vividly remembers the day the life changed forever.

It was on September 28, 2002. A young Babutty, dressed in striking costumes, waved with enthusiasm to the crowd from the circus ring. The crowd roared again for seeing the superstar of the circus ring. The galleries of the Circus Gemini in Gwalior, Madhya Pradesh, were packed with their capacity.

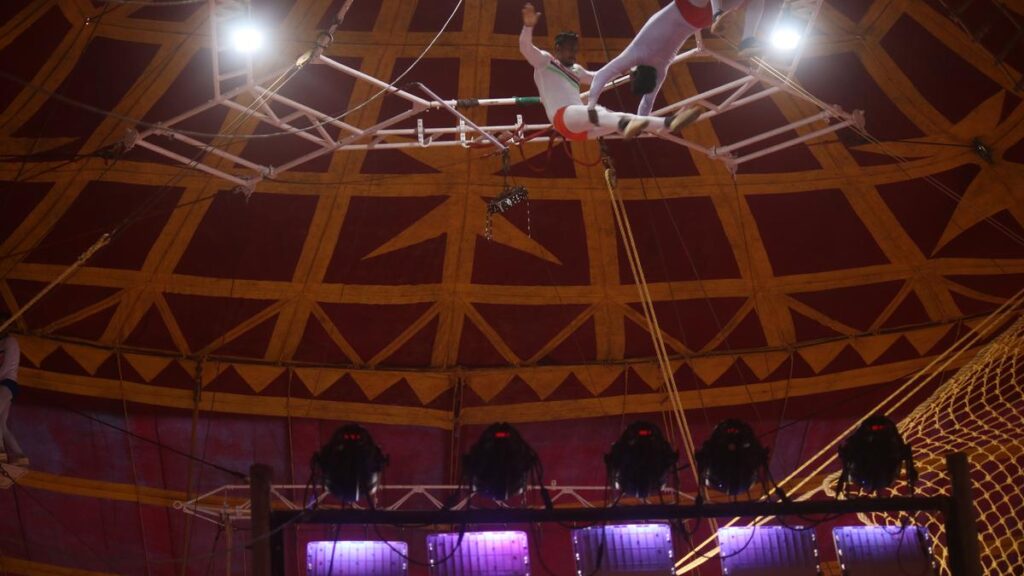

He had to perform a cross adjustment routine, a daring act in which an artist rises to the strings, while the other falls, with the help of two receptors prepared to catch and throw the artists.

Unfortunately, while swaying, an artist could not let the receiver go on time, forcing them to grab Babutty with just one hand. The receiver could not hold it. When his grip loosen up, Babutty got out of the receiver’s hand and fell to the side of the network on his back.

Babutty, a circus artist who has been working for 23 years after a trapeze fall. | Photo credit: Nainu Oommen

There was a deafening moment or silence. Then the crowd left a collective gasp. There was panic everywhere. The world stopped for Babutty.

“When I regained consciousness, I could feel numbness in the spine. I tried in vain to move my limbs,” recalls a worn chatuty, which has been working for 23 years. It was poverty that led him and his older sister, Sheela, to the circus owned by his neighbor Mv Sankran, the founder of Gemini Circus.

“In those days, there would be five or six children in a family, and one or two would be sent to the circus. These children would work there, and their parents would raise the other children with the circus profits,” explains NK Vijayendran, a senior circus artist, sitting next to Babutty.

Ramanathan, now a septuagenarian, was born in the circus. His parents, Raghavan and Devaki, were circus artists. “My father was the owner of Ranjini Circus. Or my ten brothers, I only joined the circus. The rest made a race elsewhere,” says Ramanathan, while he limits back home along the roads of the Thalasserry. The fall he suffered a few days ago left him partially limping. Ramanathan is now a shadow of his best years. So is the circus industry.

SC order, a blue bolt

The fall of the Indian circus, say the older artists, Begen 14 years ago when the Supreme Court prohibited the use of children and adolescents under 18 in circus.

This left the circus camps populated with artists in gray hair, and some take jobs as coaches. Local artists were replaced by those of Nepal, Africa and Russia.

“Sankarettan (MV Sankran) treated us as its own children. The company regularly brought us food and clothing and paid a weekly assignment. The food was also excellent. On Sundays,” Ramanath recalls.

K. Narayanan, who was popular as ‘Trapeze Flying’ Narayanan last her peak. | Photo credit: Nainu Oommen

K. Narayanan, once popular known as ‘Trapeze Flying’ Narayanan, joined the circus when he was a class V student. “He didn’t want to study then. Besides, we did and had enough resources to meet my educational expenses,” says Narayan.

For many women like Vijayalakshmi, originally from Thalassery, who did not follow his education, a circus work was an opportunity to win. He joined the Great Oriental Circus at the age of four. His aunt took her there.

See the world, through the circus

She remembers how the work made her places like Malaysia and Singapore, where she would not have gone otherwise. “We travel throughout India and act in almost all the main cities,” she says.

The artist, who uses us to do equilibrium and bike acts with well -stretched strings, remember to have brought home a Panasonic radio after a Singapore tour a few decades ago and how the reverence and the neighbors went mass.

Vijayalakshmi, who joined the great oriental circus at the age of four | Photo credit: Nainu Oommen

Uma Devi, Native to Thalasserry, who grew up looking at her father, Quran, training other circus artists, faced strong resistance when she expresses her desire to join the industry. His persistence won, and it is possible to the industry. However, UMA was asked to renounce the ring at the age of 19, since his father wanted him to marry and calm down. A few years later, Uma married a circus artist, Narayanan, who was not interested in continuing in the circus.

Destiny otherwise, since Narayanan was a duration of hardness seriously a team practice session in Patna. “He was seriously injured in the accident. I still remember him in a nearby hospital, all soaked with blood,” says Uma.

Narayanan had to undergo prolonged medical treatment, and poverty forced her children, Reena and Pree, four and six years old, to join Circus. “I acted in the ring for 20 more years. With the little money I earned, I founded my husband’s treatment and married my daughters,” she says. However, it is far from being counted. “I couldn’t keep anything for old age.”

Scarce monthly pension

Many artists obtained land plots from circus owners. Vijayalakshmi is one of them and builds a house in tenure. Many feel that Kerala circus artists are relatively better than their counterparts in other states, thanks to the government’s decision to provide them with a monthly pension of ₹ 1,600. In Kerala, as the pension offers many circus artists retired from Axis 1.113, says P. Vishnuraj, director of Sports and Youth Affairs.

Circus artists, however, point out how difficult it is to prosper in such a meager amount. “Medications and allied medical care expenses and the cost of living have skyrocketed,” says Batchutty.

A previous attempt from Kerala Sangaetha Nataka Akademi to provide circus artists a medical insurance plan had not advanced. DIVYA S. IYER, Director of Cultural Affairs, hopes to relive the proposal. “We can review the proposal of an insurance plan for artists,” she says.

Government. Use of prohibitions or animals

The descending sliding of the circuses and the life of the artists accelerated by the government’s decision to prohibit the use of animals in trade in the late 90s.

He thought that many units replaced animals for robotics, did not have much charm for circus enthusiasts. Industry veterans say that the emotion of seeing elephants, bears and lions work when robotic animals present the same acts.

“People used to come to the circus mainly to see wild animals from closed rooms,” says KP Rajan, a coach and mechanic with Jumbo Circus. “Previously, we had 18 elephants with Jumbo Circus. Lions, bears, monkeys and parrots were among the proud possessions of the company. The prohibition of animals has hit us strongly,” says Rajan, sitting in a tent of the Jumbo camp and workers of Werkersers’ properties in trucks.

Except for the big names of the industry such as Gemini, Jumbo, Apollo and Great Bombay Circus, most other players have left the scene forever. “The smallest circus groups in northern India are struggling to stay in the aflism,” Rues E. Ravindran, a Jumbo Circus coach.

“Life has left this industry, which is in its years of sunset. It is just a time of time before they resume once the curtains. There are no new artists, practice sessions or coaches. The end fast,” hey adds.

Divya says that Circus has remained unchanged in his childhood days. “The industry could not keep up with changing times. It must remain to stay relevant to the youngest public,” says the bureaucrat.

A little too late for revival

PR Nisha, author of the book Jumbos and Jumping Devils: A Social History of Indian Circus He feels that it could be too late for the revival of the circus.

“I feel that it is quite difficult for circuses to recover from the impact of the prohibition of animals and use children. Both decisions have spelled fatality for industry,” he says.

Even veteran artists admit that the circus has lost its charm, which is almost impossible to restore. “Circus no longer excites us,” admits Nalini, a former artist of the great Rayman Circus.

Gone are the days when the arrival of the circus team in a city or the countryside created waves in the area and the people who bought tickets. Like its gray artists, the industry is also slowly yielding to the inevitable. However, the legacy left by artists and the art form should live a long time.

Published – April 17, 2025 11:22 PM IST