The presidential forgiveness signed by Jimmy Carter in 1977, a radical invitation to thousands of Americans to return home and help heal a nation destroyed by the Vietnam War. Those who went to Canada to avoid the draft had not wanted any part of the conflict, which killed about 60,000 Americans.

Canada had sacrificed a shelter. He did not support the war and was willing to welcome, with few questions, those that crossed the border.

Many war resistant, or Draft Dodgers as they were calls, were not interested in returning when Mr. Carter made his amnesty offer. His decisions had come with high costs: family ties broken, broken friendships and, often, shame. While some acclaim those who went to Canada as principles, others considered them a coward.

Now, the 50th anniversary of the end of the war reaches another turbulent moment.

For Americans who live in Canada, the economic attacks of President Trump and the threats to the Freeary of Canada have once again worried about feelings over the United States.

I traveled through Canada and spoke with more or less dishes to the people who had left the United States, most now in their 70 or 80 years, who reflected on their decisions to leave and their feelings about both countries. This is what they had to say.

The optimist

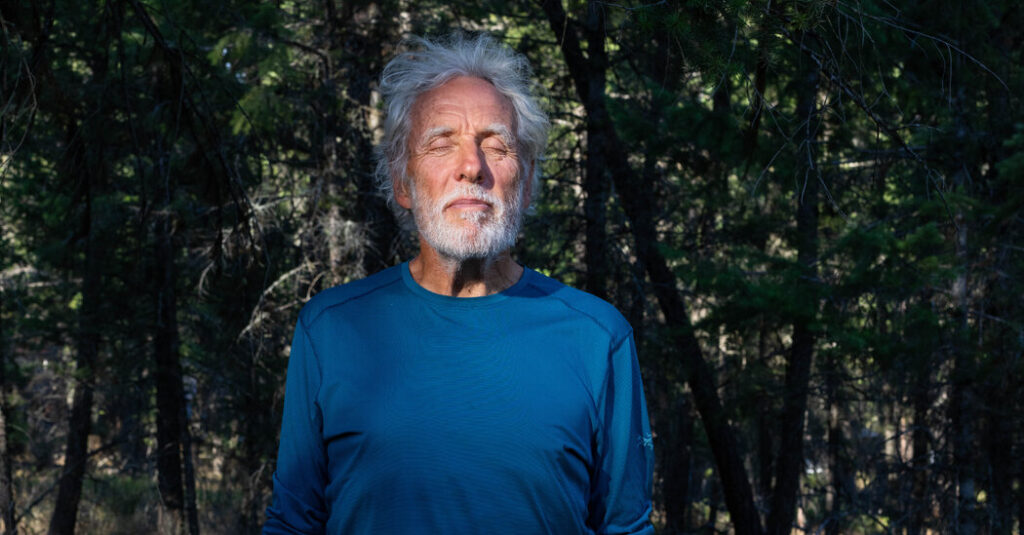

Richard Lemm saw Canada as a mythical land of beautiful views and a peaceful government.

He requested the status of conscientious objector in the United States, which was intended for people who rejected military service because it was incompatible with their religious or moral beliefs, among other reasons. He was denied and fled north in 1968.

“The main motivation to leave was political and moral,” said Lemm, a professor, writer and poet at Charlottetown, Prince Eduardo Island.

As for today, when he looks at the United States, he sees a deeply polarized society. “People are not listening enough and really need to do it,” he said.

The activism of peace in the hero of the 1960s is a great promise for Rex Weyler, a writer and ecologist who was born in Colorado.

But things changed when the FBI came to play after ignoring multiple Draft notices. Mr. Weyler fled to Canada in 1972 and now lives on Cortes Island in British Columbia. Then he became the founder of Greenpeace, the environmental group.

In recent months, he said, several people in the United States have asked their thoughts about coming to Canada. In this case, he said, he does not believe that leaving is the correct answer.

“You really can’t escape the political opinions you don’t like,” Weyler said.

The family

Don Gayton spent two years serving in the peace body among poor farmers in Colombia. When he returned to the United States in 1968, a warning draft was waiting for him.

“My country had sent me to help peasants in Colombia,” Gayton said. “And now they want them to kill them in Vietnam.”

Mr. Gayton and his wife, Judy Harris, packed their belongings and two children and went to British Columbia in 1974.

The couple’s departure led to a crack of a decade with Mr. Gayton’s father, who was furious because his son had turned his back on his military duty.

“We were proud of it, that we were firm,” Gayton said. “The shocking part is that people will never forgive war resistant.”

Looking for an authentic life

Born in Los Angeles from a family of hunters, Susan Mulkey was a vegetarian.

At age 20, he played a bus to British Columbia because he opposed war and wanted to pursue a environment more environmental oriented.

Now he lives and works in community forestry in Kaslo, British Columbia, but has ventured into American political activism, helping expatriates to vote in US elections.

“Canada facilitates my ability to live an authentic life,” he said.

The environmentalist

In 1969, Pierre Elliott Trudeau, Prime Minister of Canada, declared that the state of American youth state who moved to Canada was not relevant to allow them to legally enter the country.

That was a reason why John Bergenske moved to British Columbia in 1970 after the United States granted him the status of a conscientious objector.

“I left because I fell in love with this landscape,” Bergenske said. “Politics was secondary.”

He focused on environmental work and was the executive director of Wildsight, a non -profit conservation organization.

“If you are going out of your country of origin, you must be sure that where you are going it is a place that you really love,” Bergenske said.

Three generations of Ed Washington’s family served in the United States army. They were black and considered that the most hospitable army than the civil world.

“My grandfather felt that it was the least racist place for him,” said Washington, a legal assistance lawyer in Calgary, Alberta.

His mother, a Quake, sent Mr. Washington to a Quadero boarding school in British Columbia. When he returned to the United States to attend university, he applied the status of conscientious objector because pacifist beliefs and taught in a Quaquera school in California, where he with Jerry García and immersed himself in the rock subculture ‘N’ Roll.

But Mr. Washington said he looked into drug use in his circles and returned to British Columbia in 1974.

It has spent a lot of time thinking about the past. “I simply thought I would interfere with me to live my life today,” he said.

As a university student in the state of Washington, the draft policy allowed Brian Conrad to defer his military service whenever he enrolled in school.

After completing his studies, he made Costop through Latin America in 1972, anyone married and used his double Canadian citizenship to move to British Columbia, where he spent 30 years as a secondary school teacher and environmental activist.

Mr. Conrad has considered returning to the United States, but two things keep it away: strict control of fires and their public medical care system in Canada.

Still, he said: “I don’t want to paint with roses and the other with thorns. We have our challenges and problems.”

The pacifist

Ellen Burt grew in a Quaquera family in Eugene, Oregon, formed by a culture that opposed many US policies, even before Vietnam’s war.

At 19, Mrs. Burt decided that she wanted to live in the desert. He traveled to British Columbia, where he had connections with the Quakers who lived there.

He started reopened while he cultivated and cared for and celebrated seasonal works.

He never considered returning to the United States because his relatives there supported his movement a lot. Today, however, he said that he feels that Canada does not have the same reputation of being a shelter.

“This acquisition of right -wing governments is happening worldwide,” he said.

The mountains were calling

Canada felt more like a giant backyard than a separate country to Brian Patton. The border was a short distance from his work in Montana as rangers.

After taking a wounded woman to the other side of the border to a hospital in Alberta on a 1967 night, they decided to live in the Canadian rock mountains.

He ignored a warning draft by mail, became Canadian citizen and wrote a hiking manual called “The Canadian Rockies Trail Guide.”

The mountains were the sanctuary of Mr. Patton, said: “The sanity was just one step through the border.”

The politician

When his warning draft arrived, Corky Evans stayed with the rules and tok a physical examination of the army. Passed.

Mr. Evans tried to obtain the status of conscientious objector, but his Christian minister refused to write a support letter.

He married a woman with children of a previous marriage and moved to Canada.

He became a child care worker on Vancouver Island and worked on strange jobs before running for a provincial office, which led to a long career in British Columbia politics.

“Canada let me build a life here,” Evans said.

The father

Bob Hogue was serving in the army and parked in the prison in San Francisco, at that time an army base, where he downloaded the bags of the bodies of the US soldiers who had died in Vietnam.

He feared the moment he would be called to the front line.

When the day came, he decided to go to Awol. He said he could not bear the possibility that his 1 year son grows without a father.

In 1969, he crossed the Canadian border with his wife and son.

“Not once I felt guilty about that or that I was betraying my country,” said Hogue, who lives in northern British Columbia.

He took it in several works, including fire strips and carpentry, before an Oaly that has a small registration company. Even so, Mr. Hogu never renounced his American citizenship and feels an affinity for the country he left.

“I’m worried about the state of our world,” he said.

Vjosa Isai Toronto contributed reports.